Automatic diagnosis of Alzheimer's Disease - where are we?

During my three years of doctoral project, which ended in December 2015, I studied the implementation of an intelligent system able to automatically classify patients with Alzheimer’s Disease (AD).

As you all know, AD is the most common neurodegenerative disease, affecting millions of people worldwide. Although this condition has been known for more than a hundred years, there is still no definite diagnosis. More difficult than this, diagnosing Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) -which can be simply described as a pre-clinical and pre-symptomatic condition that may (MCIc) or may not (MCInc) convert to AD- is one of the biggest challenges in medicine.

Predicting the conversion of MCI to AD is one of the biggest challenges

These considerations alone are able to explain the great race of the last few years for the implementation of machine learning algorithms able to automatically diagnosing AD and/or predicting the conversion of MCI.

The great race for machine learning in AD

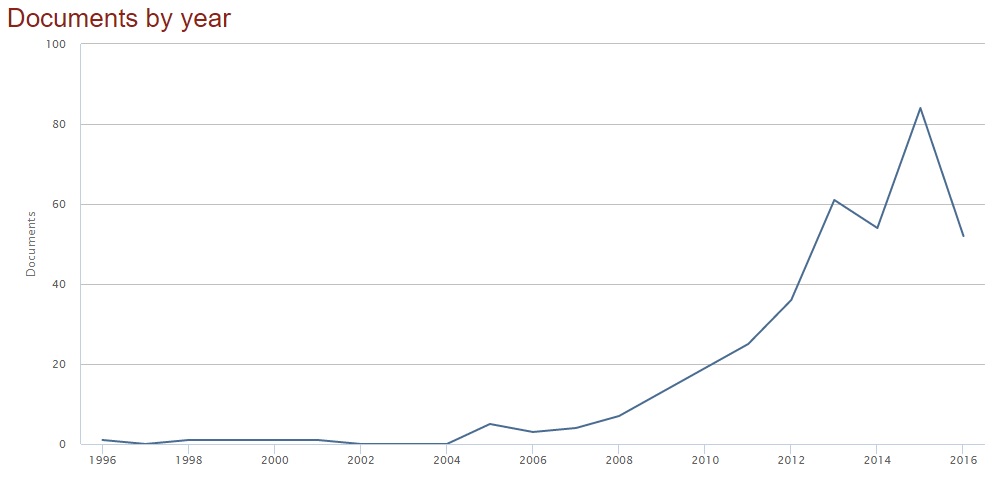

In the last few years, there has been a great race for the implementation of automatic algorithms for AD diagnosis. More explanatory than words, if you type the keywords “machine learning” and “alzheimer” in the search form of scopus, you will obtain this plot (search fields: article title, abstract, keywords; date: October 2016).

But what is the modality used as input to the classification algorithms?

Just to give a rough estimate, of 368 retrieved papers, the majority (98) contains the keyword MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging). Then we go from biological (69), to genetic (50), to PET (Positron Emission Tomography, 40), neuropsych- (neuropsychological test scores, 33), amyloid (28), down to CT (computerized tomography, 4).

As expected, MRI -in particular structural MRI- is the most used modality when we deal with neurological disorders. This is probably because it represents a good compromise between sensitivity (to brain changes due to the disease) and non-invasiveness. For example, PET is more sensitive to functional brain alterations even preceeding structural changes, but its invasiveness is a big negative point.

Structural MRI is the most used modality for the automatic classification of AD

The second question may be which feature-extraction/classification method is the most used? - but we will not go through this topic in this post. We would rather want to know what is the classification performance of these methods, that is, of the methods published in these (almost) 400 papers. This should answer to the most general question that is the title of this post - Automatic classification of AD: where are we?

Surprisingly, if you go through all these papers, you will note a strange distribution in classification performance: there will obviously be no published papers with very poor performance (under chance); there will be some papers with conceivably-average performance; but you will also find a lot of published papers with incredibly excellent performance, including perfect or quasi-perfect classifiers!

Let’s take, for example, the basic -yet nontrivial- diagnosis of AD. In this case, the classifier is asked to discriminate between patients with AD and Cognitively Normal (CN) subjects (AD vs CN). If you have a look at the papers, you will discover that the major part of the published algorithms is able to obtain classification performance (accuracy/number of correct predictions over the whole test dataset) beyond 85%, some reaching 100% classification accuracy.

So, how is this possible? We are not able to classify handwritten digits with 100% accuracy yet, but we can say if a patient has AD with no errors? Well, may this be due to the fact that AD and CN are easily-separable groups - given the deeply different characteristics of a normal brain (we are talking about structural MRI here) with respect to the brain of a patient with AD?

Let’s have a look at a much more complicated task, then: the prediction of conversion of MCI to AD. In this case, the classifier is asked to discriminate between patients with MCI who will convert to AD and patients with MCI who will not convert to AD (MCIc vs MCInc). Obviously, as we don’t know how to figure out if a patient will or will not convert to AD, the final diagnosis is obtained by following patients up for a given period of time (say, 18/36 months) and by using the diagnosis at that time (AD or still MCI) as final gold standard to evaluate the predictive power of our classification algorithm. In this way, baseline (time zero) data are used for training/validation/testing of the classifier, while follow-up labels are used as gold standard for evaluating classification performance.

Again, if you have a look at these papers, you will discover that classification of MCIc vs MCInc can easily go beyond 70%, which is an excellent result for such a huge problem, still reaching nearly 100% accuracy in some cases.

Ok, so probably the diagnosis and prediction of conversion to AD is not a big problem. We got it? Not exactly.

- Cuingnet et al., 2011

In 2011, Remi Cuingnet and colleagues [1] decided to take ten different machine learning methods, which had already been tested for automatic classification on different datasets, and to apply them to the classification of the same dataset of patients. In this way, they were sure to have a common benchmark on which different algorithms could be compared basing on their classification performance. This set of patients was obtained from a public dataset (the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, ADNI) in order to make results reproducible, and IDs of patients were made publicly available. A total of 509 patients was retrieved, including 137 AD, 76 MCIc, 134 MCInc and 162 CN. Structural MRI images (T1-weighted at 1.5T) of these patients were used, and the following binary comparisons were performed: AD vs CN, MCIc vs CN, MCIc vs MCInc.

What turned out to be the classification performance of these methods on a unique dataset?

Results showed that automatic classification of AD vs CN ranges from a minimum of 70 to a maximum of 88% (balanced accuracy), classification of MCIc vs CN from 60 to 82%, and classification of MCIc vs MCInc from 50 to 68%.

Prediction of conversion to AD reaches an accuracy of 68%.

A big difference with respect to the performance obtained on individual datasets!

- The CADDementia grand challenge (2015)

An initiative similar to the previous one (in terms of aims and results) was carried out by Bron and colleagues [2] a few years later, in 2015. In this case, they set up a challenge, which is much closer to what actually happens in fields like computer vision, where different algorithms are evaluated on big datasets through public competitions. In this particular case, organizers provided structural MRI images (T1-weighted @ 3T) of 384 patients (including 112 AD, 131 MCI and 141 CN) to researches/competitors, who had to classify a (testing) subset and return classification labels, which could in turn be used to evaluate the performance of each individual algorithm. The aim of the competition was clear:

In this challenge, we aim to take a step forward to the clinical use of computer-aided diagnosis methods for dementia by performing a large-scale objective validation. To compare the performance of image-based diagnosis methods, all researchers are invited to participate with their algorithms.

Unlike previously cited cases, this time the evaluation was made for the multi-group classification of AD vs MCI vs CN, which is slightly more difficult than performing binary classification tasks. However, in this case the MCI group was not splitted into MCIc and MCInc, which, on the other hand, turns out to facilitate the discrimination. Another peculiarity of this competition is that the provided training set was not so large, so researchers were allowed to use independent cohorts to train their classifier (obviously, the testing set remained fixed, instead).

The performance obtained in this competition can be found directly on the webpage of the CADDementia challenge and, as it can be seen, original results ranged from 32 to 63% for the multi-group classification of AD vs MCI vs CN.

Not so good.

Finally: a good feature of this competition is that the challenge remains open for new submissions. So, if you can do better than this, what are you waiting for?

Some considerations

The big gap between performance obtained using individual datasets and performance obtained on public/shared ones can be primarily ascibed to the chioce of the dataset. Indeed, researchers always tend to choose datasets/subjects that are as clean as possible, but this always results in overestimating the performance of a classification algorithm. In other words, we obtain good results (also) because the group of patients that we are trying to discriminate is -in fact- easily separable, and we’d probably obtain high performance even with much more primitive classification algorithms.

As pointed out in a recent review by my research group [3], in order to avoid this issue, publicly available databases should always be used to evaluate the performance of a classification algorithm on a given pathology. For example, ADNI and OASIS are two popular choices providing data of patients with AD.

A few other examples

- Moradi et al., 2015

Other examples of this simple principle are present in recent literature. In 2015, Elaheh Moradi and colleagues [4] published a paper in which they tried to automatically classify MCI patients using structural MRI from the ADNI database, using a cohort of 200 AD, 164 MCIc, 100 MCInc and 231 CN. Their algorithm resulted in an accuracy of 75% for the classification of MCIc vs MCInc. The authors of the paper published the IDs of the patients used in their work, thus making future comparisons possible.

Moreover, a further analysis was present in their paper: in order to compare their performance with the work by Cuingnet and colleagues [1], the authors performed the same experiments (i.e., with the same classifier and configuration) using training and testing set used in their manuscript. The performance obtained was 68% (balanced accuracy), that is lower than the accuracy obtained using their own dataset and is equal to the maximum accuracy obtained in the original paper by Cuingnet et al.

- Salvatore et al., 2015 - my own experience

In the same year, my research group published a paper [5] in which we used the same dataset employed in the paper by Cuingnet et al. [1], but with a difference in the validation process. While the original dataset had been splitted into training and testing set by Cuingnet and colleagues, performing first a leave-one-out on the training set for validation and parameter optimization and using the testing set for performance evaluation, we used a 20-fold nested cross-validation, in which parameter optimization was made in the inner loop of the nested CV and performance evaluation on the outer loop. This did not allow us to perfectly compare the performance of our classifier with results published by Cuingnet, even if a rough estimate could still be made.

Our classification algorithm reached a balanced accuracy of 76% in classifying AD vs CN, 72% for MCIc vs CN and 66% for MCIc vs MCInc. Both IDs of patients (from ADNI) and nested-CV splitting are published online, with the aim of allowing future (as unbiased as possible) comparisons.

Classification performance: state of the art

Automatic classification and diagnosis of AD, especially in its early stage (MCI), is not so simple as it may appear from a brief glance at the huge amount of papers published on this topic. Indeed, we saw that we are far away from a definite answer to this problem and that a lot of research must be done in the future if we want to tackle this issue. At this page you can find a summary of the state-of-the-art classification performance of AD using public datasets of structural MRIs. In particular, I listed all datasets described in this post (Cuingnet-509, Moradi-825, Salvatore-509 and the CADDementia dataset) and the performance obtained in published papers. Please, feel free to fill in the form or to contact me if the list is not up-to-date or if any data is missing/wrong.

While I am writing this post, automatic classification of AD (vs CN), as well as MCIc (vs CN), seems to be possible with around 90% accuracy. On the contrary, prediction of conversion to AD (MCIc vs MCInc) still seems to be below 70%. All this in a simplified binary non-clinical contest.

What will be in the future?

References

[1]: Cuingnet, R. et al. (2011). Automatic classification of patients with Alzheimer’s disease from structural MRI: a comparison of ten methods using the ADNI database. NeuroImage, 56(2), 766-781.

[2]: Bron, E. et al. (2015). Standardized evaluation of algorithms for computer-aided diagnosis of dementia based on structural MRI: the CADDementia challenge. NeuroImage, 111, 562-579.

[3]: Salvatore, C. et al. (2016). Frontiers for the early diagnosis of AD by means of MRI brain imaging and support vector machines. Current Alzheimer Research, 13(5), 509-533.

[4]: Moradi, E. et al. (2015). Machine learning framework for early MRI-based Alzheimer’s conversion prediction in MCI subjects. NeuroImage, 104, 398-412.

[5]: Salvatore, C. et al. (2015). Magnetic resonance imaging biomarkers for the early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: a machine learning approach. Frontiers in neuroscience, 9.